The Jellyfish Who Lost Hope

Hydras and the Roots of Depression

British soldiers attending a popular science lecture in the nineteenth century were shown creatures in a drop of pond water projected onto a screen from an instrument called a lantern microscope. The soldiers “looked on with intense interest” when a water flea became entangled in the stinging arms of a Hydra, and “made the most violent efforts to escape, turning over and over, amid excited murmurs from the soldiers.” When the water flea “hurled itself free . . . every man in the room sprang to his feet and joined in a deafening cheer.” They had empathized with the combat on the microscope slide, recognizing the Darwinian “struggle for life” in these simple organisms. Reading this story, I am more interested in the response of the Hydra to its failed attack, and the possibility that this tiny relative of jellyfish felt dejected. Because, despite their brainless nature, hydras are liable to depression.

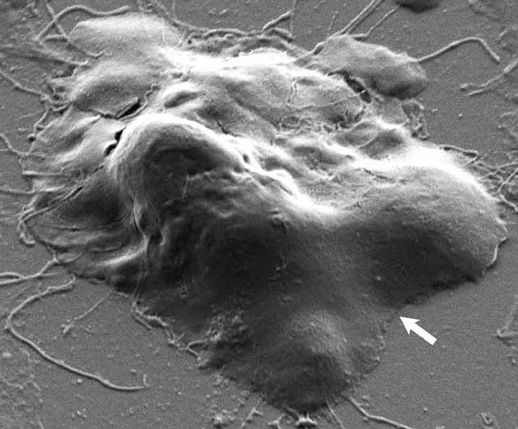

Hydra is the Latin name for more than 20 species of freshwater invertebrates that are around one millimeter in length and extend multiple tentacles covered with stinging cells that fire poisoned barbs into their prey. This jellyfish relative has been used as for research on developmental biology since its discovery in the eighteenth century when investigators marveled at its remarkable powers of regeneration. When hydras are cut into pieces, whole animals regrow from each of the severed parts. Hydras have two layers of cells, the ectoderm and endoderm, but lack the middle mesoderm layer from which the skeleton, muscles, and organs develop in more complicated animals like us. Under a microscope, the stingers are evident as blobs that run the length of their arms and give them the look of beaded necklaces. The hydra waves its arms through the water, flexes its cylindrical body, and moves from place to place by detaching and reattaching its adhesive foot.

A hydra does not have a permanent mouth, but opens a fresh one in the middle of its tentacles each time it feeds. As the mouth widens, the hydra swallows the water flea or other pond creature whole, distending its body like a boa constrictor. The water flea has a brain that connects to its single eye and processes signals from its environment and coordinates its evasive actions when it is caught by a hydra. Its use of neurotransmitters and hormones common to most animals suggest that it engages in an emotional life of rewards and punishments that relies on the same elementary mechanisms that control our actions and thoughts. Water fleas do not worry about the future, but they are flooded with stress hormones when they are stung by a hydra. But what does a hydra feel?

The brainless Hydra uses two networks of nerves to control its movements. One is located in the outer layer of cells, the ectoderm, the other within the endoderm that lines the digestive cavity. Lacking a brain, it does not send and receive nerve impulses from different parts of the body at the same time, but its nerve webs coordinate a whole-body response when it captures a water flea, moves toward sunlight, or contracts in response to an injury. And, surprisingly, hydras express traces of an emotional life in periods of reduced activity in which they contract their bodies and arms and condenses into a ball, or simply lie flat on their side. Hydra experts have called this depression for more than a century without implying any relationship to human unhappiness. This anthropomorphic extension is mine.

Depression in hydras was studied by German biologists in the early twentieth century who found that the animals suspended their usual activities in response to a variety of environmental changes including poor water quality, the provision of too many water fleas, and increased temperature. Even the process of collection from ponds and transfer to an aquarium makes them close down. This is reminiscent of the desperation expressed by killer whales taken from the ocean, who refuse food until they are force fed by staff in marine parks. Hydras can be saved by force-feeding them with water fleas stuck on the end of a glass pipet.

The reactions in hydras are associated with the shedding of cells into the digestive cavity and can be viewed as mechanical responses to damaging environmental conditions, like our physiological symptoms of sunburn or food poisoning. But there is more to this. Seeking treatments to keep her colonies of hydras alive in her lab at the University of Chicago in the 1920s, biologist Libbie Hyman found that transferring depressed animals to an aquarium in which other hydras were flourishing had a miraculous effect: “The beneficial effect . . . is almost incredible . . . Depressed specimens that have refused to feed for several days may accept food within fifteen minutes after being placed in a culture containing healthy hydras.”

Extending Hyman’s observations, Sivatosh Mookerjee, an Indian developmental biologist, observed that hydras kept in the laboratory fell into a state of depression every winter. Using the degree of body and tentacle contraction, digestive activity, and the speed of regeneration when they were sliced apart, Mookerjee categorized his animals on a scale of increasing depression. Most of the hydras seemed slightly depressed and could be nursed back to health, whereas the highly depressed specimens seemed to have passed the point of no return and fell apart cell by cell.

It is tempting to recognize simple expressions of the depressive disorders recognized in big-brained animals in these stress responses. The absence of a brain may seem to exclude the possibility of consciousness, but the sophistication of the brainless hydra is evident in its daily cycles of unconsciousness or sleep. Hydras sleep according to a predictable rhythm between periods of physical activity, take longer to be aroused by a flash of light when they are asleep, and sleep more when they are treated with melatonin. Dopamine pushes them into a deeper sleep, which is the reverse of its excitatory effect on us. They also respond very negatively to sleep deprivation imposed by vibrating their containers, with sluggish responses to all manner of stimuli and associated changes in gene expression.

When the amazing regenerative powers of Hydra were discovered in the eighteenth century, the little jellyfish became a sensation among European intellectuals. It was showcased in the salons of pre-revolutionary France and was described by a Dr. Gilles Auguste Bazin, a prominent natural historian, as “a discovery in a word that disconcerts the entire nation of reasoners.” Voltaire was captivated by hydras that he watched in a jar kept on the mantlepiece of a friend’s home, but refused to believe that they were animals, and Diderot fictionalized them as human polyps that lived on Jupiter and Saturn in his philosophical dialogue, d’Alembert’s Dream. Inspired by hydras, the philosopher Julien Offray de La Mettrie, advanced a theory of mechanistic materialism that culminated in L’homme machine (Man a Machine), published in 1747. La Mettrie was struck by the uniformity of nature in which humans differed from other animals in our degree of complexity rather than any essence. He also argued that the regeneration of whole hydras from their dissected parts demonstrated that the spirit or soul of an animal was inseparable from its body. As far as he was concerned, Cartesian dualism died with the discovery of the hydra.

When news of the discovery spread to England, hydras sent from Holland and found in ditches around London captivated the gentlemen of the Royal Society. In his 1768 poem, Isabella: Or, The morning, Sir Charles Hanbury Williams, recounts the description of the hydra to an unnamed duchess in her country house by a visitor from London, as “The wonderfuls’t of all the works of nature,” which causes the lady to exclaim, “Lord I must see it, or I’m undone.”

Conscious or not, hydras are fascinating animals that offer biologists and philosophers a bridge between species with brains and the majority of life, which is brainless, and microscopic. Resorting to some rather punishing experimental procedures, hydras can even show what can be done in a seemingly conscious fashion without a nervous system. If the stem cells are eliminated from hydras using radiation or chemical treatment, the animals lose their nerve nets over several weeks because they cannot replace the neurons that are dissolved through a natural cycle of tissue replacement. The loss of the nervous system results in changes in the shape of the animal, reduced sensitivity to mechanical stimulation and light, but no changes in movements or feeding behavior. Robbed of nerves, the hydra is left with a good deal of its behavioral complexity, although the symptoms of its melancholia have not been observed.

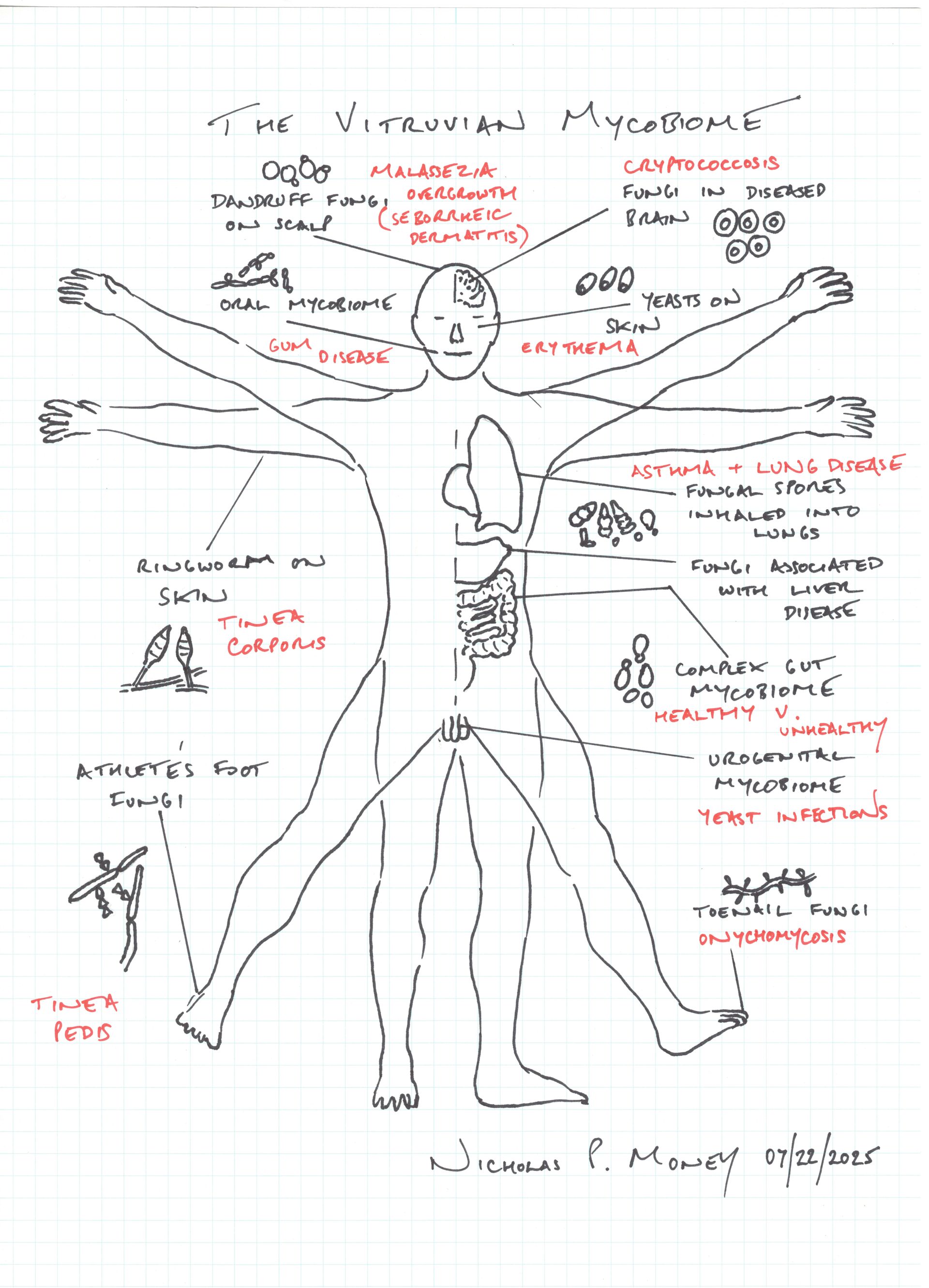

The behavior of hydras overlaps with the sensitivity of slime molds, fungi, and even single-celled amoebas, which some biologists regard as consciousness. Waving its tentacles, Hydra offers a model for the deepest roots of our mental anguish, demonstrating the sensitivity of all organisms to the exigencies of their environment. There is some solace, perhaps, in recognizing that we are united with the rest of nature in our propensity toward sadness. We share the need of these jellyfish relatives for a clean place to live in the company of other animals.